Inane rambling and musings from Ian McKerchar, sometimes hopefully not so inane...

Please note that opinion and comment within this section are entirely my own and do not represent those of the Greater Manchester Bird Recording Group or its Rarities Committee, unless otherwise stated.

Please note that opinion and comment within this section are entirely my own and do not represent those of the Greater Manchester Bird Recording Group or its Rarities Committee, unless otherwise stated.

THE SMELL OF NOSTALGIA

June 2017

“nostalgia |nɒˈstaldʒə|, noun [mass noun], a sentimental longing or wistful affection for a period in the past”

I’m not an overly nostalgic person or atleast I didn't think I was. Sure, I often long for the days when birding was simple, uncomplicated and frankly just about the birds but that’s as much in resistance to ‘modern’ birding as it is about nostalgia, so it was something of a surprise when I recently came over all nostalgic in the most unexpected fashion. Whilst smell isn’t something you instantly associate with birding, a hobby done with eyes and ears (or increasingly with fingers and an internet connection these days), smell can often evoke nostalgia. And so it was that recently, I bizarrely combined smell, nostalgia and birding all in one go!

Wandering through a local garden centre on my way to get a coffee I happened to pass a display of Barbour jackets. I was immediately drawn towards them and as a smile widened across my face, I held one of them aloft, proudly declaring to my wife (and all and sundry around) “I used to have one of these”! As I held it aloft, not realising that these days they’re so expensive they have little alarm wires thread through them, something hit me; the smell! That slightly musty, oily smell of the jacket took me back to the time when I owned one way back in the 1980s and I was instantly swept away in a wave of nostalgia.

Of course, back then Barbour jackets were de rigueur for birders and pretty much everyone had one. Gore-tex, though invented in 1969, was only really available in brightly coloured golf or high-end mountaineering jackets back in the 1980s and so it was Barbour who birders turned to in their pursuit of a hard-wearing waterproof jacket which blended into foliage. And they served us well too. They were indeed waterproof (initially at least), came in drab green or brown colours, had big pockets for notebooks (yes everyone had one back then) and mars bars and were pretty robust to boot. I still remember my own very fondly indeed, being a faithful companion on daily birding outings, regular national twitches (and dips!) and many birding holidays. Whilst it started out as a pristine, perfectly manufactured garment, the hard labour of intensive birding quickly took its toll yet gave it its undeniable character. It cracked and wore through at the creases, smelled musty, oily and more than occasionally just downright awful and the fabric got greasy in warm weather or became rock hard in the cold. But like an old leather Chesterfield sofa it had character, a ‘lived in’ look and feel which only came via heavy usage and became almost a badge of honour, proof to all that you were a ‘hard-core’ birder. Of course, eventually those cracks and wear points leaked when it rained and the lack of maintenance (you were supposed to re-wax it every so often but it never got done) saw its overall water repellency fall off until it merely absorbed water like a paper towel.

In the late 80s the old faithful Barbour was eventually put to rest, being replaced by a new Gore-Tex Berghaus jacket in almost birding-friendly dark blue. This then tour de force in waterproof garments was light years ahead of the Barbour in every respect but was soon itself replaced by the then pinnacle of mountaineering jackets with a Mountain Equipment Karakorum 2, a jacket designed to repel all that the highest peaks in the world could throw at it. Needless to say, it merely laughed at the best I could do in the face of a day’s soaking in the Cornish Penwith valleys and was itself only replaced after many years of exemplary service with an all black Mountain Equipment Kongur jacket. Its safe to say the Kongur is ridiculously capable. It’s 3-ply Gore-Tex Pro Shell Ascendor fabric is as waterproof as wearing half a dozen black bin bags, it has more pockets than I know what to fit into them and is as hard wearing as a galvanised nail, yet despite its extreme efficiency it is merely a piece of functional clothing; I admire it but I don’t love it.

Like that old worn yet ever so comfortable leather sofa, that old banger of a first car you ever owned which broke down a lot and cost you more than it was worth or the first pair of binoculars you had which were not much better than two sellotaped together toilet roll tubes but which you keep to this day gathering dust somewhere; somethings you cherish not for their functionality or value but instead for the sheer memories which using or even just thinking about them evokes. And so it was with that new and now really rather expensive Barbour jacket which brought back my young birding memories so vividly. For a good while afterwards I convinced myself I’d buy another Barbour jacket, doubtless in an attempt to re-capture the wonderful emotion of that '80s era of birding but of course it didn’t last long, not until the next downpour which the Kongur shed like the proverbial duck’s back and allowed me to cram my mobile 'phone, digiscoping adaptors, microphone, notebook (yep, still hanging onto that) and now seemingly much smaller Mars bars into its multitude of deep, expansive pockets.

Clearly, it seems there is a limit to just how far one can pursue nostalgia in the face of technology but whilst understandably embracing all the tech’ the more modern era can offer it seems I still cherish a time when you’d all huddle around the back of one of the small handful of photographer’s cars at twitches in order to buy their latest prints of rarities, curse the pips in that big red ‘phone box which signalled your money was running out but you hadn’t even got to hear about the birds you really wanted to know about yet (and the fact that the Birdline ‘phone operators seemingly all spoke so slowly in order to drag more money out of you), didn’t even know or care what DNA was let alone that bird shit had it in it and could be used to separate those practically impossible species we'd enjoy spending so much time arguing about or when reputations as a good birders were formed by actually going out in the field and looking at, finding your own and contributing to, birds.

And all that was brought about by the smell of a posh jacket! So, what's your smell of birding nostalgia?

“nostalgia |nɒˈstaldʒə|, noun [mass noun], a sentimental longing or wistful affection for a period in the past”

I’m not an overly nostalgic person or atleast I didn't think I was. Sure, I often long for the days when birding was simple, uncomplicated and frankly just about the birds but that’s as much in resistance to ‘modern’ birding as it is about nostalgia, so it was something of a surprise when I recently came over all nostalgic in the most unexpected fashion. Whilst smell isn’t something you instantly associate with birding, a hobby done with eyes and ears (or increasingly with fingers and an internet connection these days), smell can often evoke nostalgia. And so it was that recently, I bizarrely combined smell, nostalgia and birding all in one go!

Wandering through a local garden centre on my way to get a coffee I happened to pass a display of Barbour jackets. I was immediately drawn towards them and as a smile widened across my face, I held one of them aloft, proudly declaring to my wife (and all and sundry around) “I used to have one of these”! As I held it aloft, not realising that these days they’re so expensive they have little alarm wires thread through them, something hit me; the smell! That slightly musty, oily smell of the jacket took me back to the time when I owned one way back in the 1980s and I was instantly swept away in a wave of nostalgia.

Of course, back then Barbour jackets were de rigueur for birders and pretty much everyone had one. Gore-tex, though invented in 1969, was only really available in brightly coloured golf or high-end mountaineering jackets back in the 1980s and so it was Barbour who birders turned to in their pursuit of a hard-wearing waterproof jacket which blended into foliage. And they served us well too. They were indeed waterproof (initially at least), came in drab green or brown colours, had big pockets for notebooks (yes everyone had one back then) and mars bars and were pretty robust to boot. I still remember my own very fondly indeed, being a faithful companion on daily birding outings, regular national twitches (and dips!) and many birding holidays. Whilst it started out as a pristine, perfectly manufactured garment, the hard labour of intensive birding quickly took its toll yet gave it its undeniable character. It cracked and wore through at the creases, smelled musty, oily and more than occasionally just downright awful and the fabric got greasy in warm weather or became rock hard in the cold. But like an old leather Chesterfield sofa it had character, a ‘lived in’ look and feel which only came via heavy usage and became almost a badge of honour, proof to all that you were a ‘hard-core’ birder. Of course, eventually those cracks and wear points leaked when it rained and the lack of maintenance (you were supposed to re-wax it every so often but it never got done) saw its overall water repellency fall off until it merely absorbed water like a paper towel.

In the late 80s the old faithful Barbour was eventually put to rest, being replaced by a new Gore-Tex Berghaus jacket in almost birding-friendly dark blue. This then tour de force in waterproof garments was light years ahead of the Barbour in every respect but was soon itself replaced by the then pinnacle of mountaineering jackets with a Mountain Equipment Karakorum 2, a jacket designed to repel all that the highest peaks in the world could throw at it. Needless to say, it merely laughed at the best I could do in the face of a day’s soaking in the Cornish Penwith valleys and was itself only replaced after many years of exemplary service with an all black Mountain Equipment Kongur jacket. Its safe to say the Kongur is ridiculously capable. It’s 3-ply Gore-Tex Pro Shell Ascendor fabric is as waterproof as wearing half a dozen black bin bags, it has more pockets than I know what to fit into them and is as hard wearing as a galvanised nail, yet despite its extreme efficiency it is merely a piece of functional clothing; I admire it but I don’t love it.

Like that old worn yet ever so comfortable leather sofa, that old banger of a first car you ever owned which broke down a lot and cost you more than it was worth or the first pair of binoculars you had which were not much better than two sellotaped together toilet roll tubes but which you keep to this day gathering dust somewhere; somethings you cherish not for their functionality or value but instead for the sheer memories which using or even just thinking about them evokes. And so it was with that new and now really rather expensive Barbour jacket which brought back my young birding memories so vividly. For a good while afterwards I convinced myself I’d buy another Barbour jacket, doubtless in an attempt to re-capture the wonderful emotion of that '80s era of birding but of course it didn’t last long, not until the next downpour which the Kongur shed like the proverbial duck’s back and allowed me to cram my mobile 'phone, digiscoping adaptors, microphone, notebook (yep, still hanging onto that) and now seemingly much smaller Mars bars into its multitude of deep, expansive pockets.

Clearly, it seems there is a limit to just how far one can pursue nostalgia in the face of technology but whilst understandably embracing all the tech’ the more modern era can offer it seems I still cherish a time when you’d all huddle around the back of one of the small handful of photographer’s cars at twitches in order to buy their latest prints of rarities, curse the pips in that big red ‘phone box which signalled your money was running out but you hadn’t even got to hear about the birds you really wanted to know about yet (and the fact that the Birdline ‘phone operators seemingly all spoke so slowly in order to drag more money out of you), didn’t even know or care what DNA was let alone that bird shit had it in it and could be used to separate those practically impossible species we'd enjoy spending so much time arguing about or when reputations as a good birders were formed by actually going out in the field and looking at, finding your own and contributing to, birds.

And all that was brought about by the smell of a posh jacket! So, what's your smell of birding nostalgia?

The very young author on Peninnis Head, Scilly, October 1986 exhibiting the then requisite and somewhat unsuitable birding attire of dirty stonewashed jeans, muddy Reebok trainers and smelly, greasy, but loveable, Barbour jacket (photo courtesy of Andy Makin)

MEMORY BANK

April 2020

The pot of gulling gold at the end of the rainbow

Richmond Bank is a large tidal mud bank in the middle of the River Mersey, just west of Warrington and immediately south of Penketh in Cheshire. Its proximity to the now closed Arpley Tip, a mere 500 metres to the bank’s south-east meant that at any one time, provided the tide was out and bank exposed, up to 10,000 gulls could be seen loafing on the mud there, with anything up to 30-40,000 gulls in the whole area. It was not just the sheer number of gulls present which made the site a gull-watching utopia either, for the whole viewing experience was without equal.

Arpley Tip was eventually closed in December 2017 and that fateful day sounded the death knell of gull watching at the bank. My long-time gulling partner Pete Berry and I spent hundreds of hours over many years watching the gulls there, with generally two trips a week throughout the winter months, often increasing to four on occasion and with more sporadic though still fairly regular visits during the rest of the year, even mid-summer! It genuinely became a home from home to us, our happy place, but its closure left a huge gulling-void which has yet to be satisfactorily filled.

Possibly as part of my own final (and seemingly still ongoing) acceptance of the passing of that huge gull watching chapter in my life, I offer some bite-sized musings from over the years, few of which involve much to do with gulls it has to be said!

Arpley Tip was eventually closed in December 2017 and that fateful day sounded the death knell of gull watching at the bank. My long-time gulling partner Pete Berry and I spent hundreds of hours over many years watching the gulls there, with generally two trips a week throughout the winter months, often increasing to four on occasion and with more sporadic though still fairly regular visits during the rest of the year, even mid-summer! It genuinely became a home from home to us, our happy place, but its closure left a huge gulling-void which has yet to be satisfactorily filled.

Possibly as part of my own final (and seemingly still ongoing) acceptance of the passing of that huge gull watching chapter in my life, I offer some bite-sized musings from over the years, few of which involve much to do with gulls it has to be said!

Whether Jeremy Kyle actually has any interest in gulls I’m not entirely sure, though I sincerely doubt it. I could certainly imagine him joining in the mass heated and generally futile debates on Birdforum though, his pompous and unqualified gabble on ‘cactus’ gulls fitting in well without the need for ‘Security Steve’s’ protection. But no, I digress, Jeremy Kyle isn’t into gulls. To be fair, I’m not a Jeremy Kyle fan anyway, not at all. In fact, his show (now cancelled after the tragic death of a contestant) was everything I despise on TV and indeed in modern society and yet boy, could he fill the void of a period of inactivity.

It was during one of these periods of inactivity at the bank that I was showing Pete how we could watch TV on my phone and up popped Jeremy on his morning show. Fascinated by the crassness of the man and the apparent pandemonium of the show, we’d while away many a dread and subsequent disappearance of gulls. Dreads were commonplace too. Sometimes there was an obvious reason for such a dread and just as often as not there wasn’t, but a dread is when the gulls fly up on mass, as if in panic, and as was often the case at the bank, just bugger off. Buzzards were hit and miss at causing pandemonium as were low flying aircraft going in or out of Liverpool Airport; sometimes the birds would spook easily and sometimes they’d be totally oblivious to it. It could take the mere alighting of a Grey Heron amongst the gulls and the ripple effect through the many thousands across the entire bank could clear it in seconds and leave you looking at what in essence, the bank was; a dirty great big bare piece of mud covered in bird shit. We never did work out what caused most dreads and I doubt the gulls knew either, but they were typically really frustrating, often occurring right at the moment you found something ‘interesting’ and were trying to get each other onto it. Their subsequent buggering off back towards the tip or off downstream meant we had plenty of time to contemplate the possible reasons and once bored of that, well that’s where Jeremy came in. We’d sit back, pour a brew, cover ourselves in crumbs and watch Jezza go about his thing, right up until the next wave of gulls fresh from the tip came around the bend in the Mersey to wash, rest, fight and shit; all the things a gull loves to do.

No, there’s no doubt the Jeremy Kyle show was garbage, but for two gullers who spent an unhealthy amount of time actually looking at rubbish anyway (though usually with a load of gulls on it), unbeknown to him, he became an integral part of gull watching at the bank.

8000+ gulls on blatant display meant Jeremy Kyle didn’t get a look in.

FOGGIEST IDEA

FOG noun: a weather condition in which very small drops of water come together to form a thick cloud close to the land or sea/ocean, making it difficult to see.

FOG noun: a weather condition in which very small drops of water come together to form a thick cloud close to the land or sea/ocean, making it difficult to see.

You don’t go birding in fog; fact! Well, maybe that’s not necessarily quite accurate. I’ve spent many a really productive hour in coastal fog around south-west Cornwall or East Yorkshire, but it does stand true for gulls. You don’t go gulling in fog; fact! This was first put to the test after Pete and I looked out of our respective home windows at the foggy gloom one day and optimistically thought ‘yeah, it’s not too bad and its lifting too’. I have a decent vista at the back of the house and sure enough, visibility didn’t look too bad. Too late anyway, we were in the car and off, eager for our ‘gull fix’, soon passing Winwick near Warrington to pick up a junction of the M62 before we caught a glimpse of the sky over Penketh and there was none, just, well…fog.

Our eternal optimism, borne through too many years of birding an inland northwest county, was not to be dampened and we arrived on site with a cheery ‘this’ll burn off by 11’. We set up our stalls; chairs, optics, flasks, food and set about staring at the fog. Patches of blue sky could occasionally be glimpsed over our heads but the thick bank of fog around us refused to budge, let alone be burned off by the sun. We could hear gulls too, so they were clearly not deterred from the bank and neither were we. It’s surprising how you can while away the hours chatting (and watching Jeremy go at it) and with that, 11am came and went. We opened up our sandwiches and ate them while we looked at the fog and listened to the gulls calling or was that laughing, and by 1pm we decided to call it a draw having seen no birds, let alone gulls. This was no draw though, it one one-nil to the bank but we had at least learned our lesson.

Unfortunately, unbridled optimism knows no bounds and we clearly hadn’t learned our lesson. Though we vowed never to tale our tale of stupidity, we made completely fog bound visits on four further occasions over the years, sat there for a few hours, ate our sandwiches, and went home. I even made one of those visits on my own! No, if you take only one thing away from this chapter, let it be that you don’t go gulling in fog or maybe, unbridled optimism needs to know its limits or perhaps, live somewhere you’re not forced into spending an unhealthy amount of time looking at gulls!

You don’t go birding in fog; fact! Well, maybe that’s not necessarily quite accurate. I’ve spent many a really productive hour in coastal fog around south-west Cornwall or East Yorkshire, but it does stand true for gulls. You don’t go gulling in fog; fact! This was first put to the test after Pete and I looked out of our respective home windows at the foggy gloom one day and optimistically thought ‘yeah, it’s not too bad and its lifting too’. I have a decent vista at the back of the house and sure enough, visibility didn’t look too bad. Too late anyway, we were in the car and off, eager for our ‘gull fix’, soon passing Winwick near Warrington to pick up a junction of the M62 before we caught a glimpse of the sky over Penketh and there was none, just, well…fog.

Our eternal optimism, borne through too many years of birding an inland northwest county, was not to be dampened and we arrived on site with a cheery ‘this’ll burn off by 11’. We set up our stalls; chairs, optics, flasks, food and set about staring at the fog. Patches of blue sky could occasionally be glimpsed over our heads but the thick bank of fog around us refused to budge, let alone be burned off by the sun. We could hear gulls too, so they were clearly not deterred from the bank and neither were we. It’s surprising how you can while away the hours chatting (and watching Jeremy go at it) and with that, 11am came and went. We opened up our sandwiches and ate them while we looked at the fog and listened to the gulls calling or was that laughing, and by 1pm we decided to call it a draw having seen no birds, let alone gulls. This was no draw though, it one one-nil to the bank but we had at least learned our lesson.

Unfortunately, unbridled optimism knows no bounds and we clearly hadn’t learned our lesson. Though we vowed never to tale our tale of stupidity, we made completely fog bound visits on four further occasions over the years, sat there for a few hours, ate our sandwiches, and went home. I even made one of those visits on my own! No, if you take only one thing away from this chapter, let it be that you don’t go gulling in fog or maybe, unbridled optimism needs to know its limits or perhaps, live somewhere you’re not forced into spending an unhealthy amount of time looking at gulls!

LANDMARKS

Anyone who goes seawatching regularly will know that, when you first arrive at your chosen vantage point, it’s good practice to agree static reference points out to sea which should make giving directions to other observers that much easier in the event of finding something good. Typically, they might be rock formations, islands, buoys, rigs and increasingly, wind turbines, which on a generally featureless open sea can be the difference between managing to clap eyes on that passing gadfly as folk overexcitedly shout out running commentaries and throwing yourself off the cliff onto the rocks below. Whilst the bank itself could be a featureless lump of mud and bird shit, the area around it was anything but and in the same way, reference points were absolutely essential to have any chance of getting each other onto a specific gull sat amongst 8,000 others. Conversations with those less experienced or indeed new to gull watching at the bank regularly went something very like this:

“I think I might have a Casp”

“Oh right, where about are we looking?”

“You see that Crow”

“There’s about 60 Crows out there, anything more specific?”

“It’s the one next to a Herring Gull right now”

(Looks out at 60 Crows amongst 8000 Herring Gulls on a huge mudbank) “no, still not picking that one up I’m afraid…”

We were fortunate at the bank though as there were many reference points above the riverbank and skyline. Church steeples, storage tanks, particular bushes or trees, a path, a pipeline fortuitously with different coloured sections along its length, though all of which necessitated you taking your eye off the bird in order to gauge exactly where it was to the reference point and that would often mean you’d struggle to re-find the bloody thing! There were others we could use too, those which would only last until the next high tide but like passing ships and boats or even different coloured areas of sea in seawatching, they were equally useful but often a lot more interesting.

Huge tree trunks were occasional on the bank, beached there by really high tides but at 30 feet long and weighting in at a few tonnes, they were hard to miss. Big chunks of polystyrene were popular, whilst a children’s plastic playground made a colourful marker and once, a complete front bumper of a car, although we semi-seriously suspected it was still attached to the rest of the car hidden under the mud too. Our favourite was always footballs though. Balls of all colours were strewn along the grassy bank of the river and meant you didn’t have to take your eye off the bird too much in order to pick out a unique marker. Indeed, whilst I don’t recall the exact count, though I do know it was entered into my notebook at the time, after one particular high tide I counted their numbers at one sitting alone into the low thirties! That must have been a particularly slow day though…

Anyone who goes seawatching regularly will know that, when you first arrive at your chosen vantage point, it’s good practice to agree static reference points out to sea which should make giving directions to other observers that much easier in the event of finding something good. Typically, they might be rock formations, islands, buoys, rigs and increasingly, wind turbines, which on a generally featureless open sea can be the difference between managing to clap eyes on that passing gadfly as folk overexcitedly shout out running commentaries and throwing yourself off the cliff onto the rocks below. Whilst the bank itself could be a featureless lump of mud and bird shit, the area around it was anything but and in the same way, reference points were absolutely essential to have any chance of getting each other onto a specific gull sat amongst 8,000 others. Conversations with those less experienced or indeed new to gull watching at the bank regularly went something very like this:

“I think I might have a Casp”

“Oh right, where about are we looking?”

“You see that Crow”

“There’s about 60 Crows out there, anything more specific?”

“It’s the one next to a Herring Gull right now”

(Looks out at 60 Crows amongst 8000 Herring Gulls on a huge mudbank) “no, still not picking that one up I’m afraid…”

We were fortunate at the bank though as there were many reference points above the riverbank and skyline. Church steeples, storage tanks, particular bushes or trees, a path, a pipeline fortuitously with different coloured sections along its length, though all of which necessitated you taking your eye off the bird in order to gauge exactly where it was to the reference point and that would often mean you’d struggle to re-find the bloody thing! There were others we could use too, those which would only last until the next high tide but like passing ships and boats or even different coloured areas of sea in seawatching, they were equally useful but often a lot more interesting.

Huge tree trunks were occasional on the bank, beached there by really high tides but at 30 feet long and weighting in at a few tonnes, they were hard to miss. Big chunks of polystyrene were popular, whilst a children’s plastic playground made a colourful marker and once, a complete front bumper of a car, although we semi-seriously suspected it was still attached to the rest of the car hidden under the mud too. Our favourite was always footballs though. Balls of all colours were strewn along the grassy bank of the river and meant you didn’t have to take your eye off the bird too much in order to pick out a unique marker. Indeed, whilst I don’t recall the exact count, though I do know it was entered into my notebook at the time, after one particular high tide I counted their numbers at one sitting alone into the low thirties! That must have been a particularly slow day though…

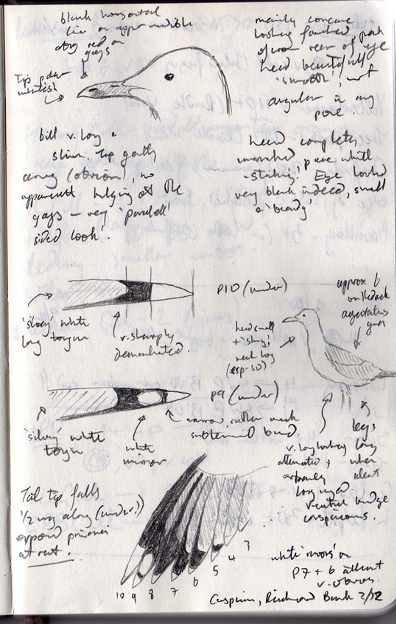

TIME AND TIDE

Timing was everything at the bank. Afterall, the River Mersey was still tidal all the way to Warrington, so getting your visit to coincide with the right tide was essential; get it wrong and the bank could be completely covered by water and devoid of gulls. Tide tables therefore became a prerequisite, but it was not just the time of the tide but its height too which became important. To maximise our available visits, we quickly worked out at what height the tide actually covered the bank. Now this wasn’t necessarily always as easy as it sounded as being made of mud, the bank was always changing shape. Sometimes it was really flat and covered very easily and others it was huge, with great three-foot sheer cliff edges which could withstand all but the very highest tides, so you just never quite knew until you got there, but we still tried our best. Only on those very highest tides was it ever covered for any real length of time though and so when the average high tide fell slap bang in the middle of our visit, we’d usually sit it out. This gave us chance to eat and drink, chat or indeed, watch Jeremy Kyle but it never lasted more than an hour, for the gulls knew when the tide was ebbing and would be quickly onto it, wading around until the first mud became exposed once more.

It was those very highest tides which became something of a fascination to us though. The really big tides above ten metres, especially the ones usually occurring in spring and autumn, would completely flood the area, very rapidly swelling the river over its banks, swamping the grassy edges. Whilst they weren’t always conducive for gulling with the height of them meaning the bank was well covered for a couple of hours at least, we still went down to catch maybe an hour or so before its peak but more importantly, to watch the tide itself. It was just a great spectacle. The sheer volume of water and speed of the deluge was impressive alone and the amount of detritus it would carry up stream (and back down again later) was remarkable. It would often flush out hidden Snipe and occasionally, one or two larger looking pipits with explosive single note calls which never did give anything other than very fleeting flight glimpses; Rock or Water…that was the question. As the water rose, the bank itself would become smaller and smaller, with the gulls corralled into a tight white horde as they fought to remain on the mud for as long as possible before being forced off back to the tip or downstream for the rest of the day as it was enveloped.

It was only on very rare occasions that we experienced the most impressive spectacle the Mersey had to offer though. It was early spring the first time we witnessed it. Pete and I were searching through the thousands of gulls as usual when I heard a noise coming from downriver, heading upstream towards us. I expected it to be a boat of some form as I couldn’t quite place the sound, a roar of kinds, and boats were occasional past the bank and a bloody nuisance to boot. As the roar became louder, it finally rounded the bend in the river and came into full view. Now, a twelve inch wall of water moving at running speed up the width of a river and against the flow might not really sound all that impressive but let me tell you…it is. Up to that point we had no idea the Mersey even had a tidal bore and it seemed neither did the equally surprised gulls but sure enough, there it was in all its, admittedly not exactly surfable, glory. So taken we were with it we would work out when the next one was likely to be and make further visits just to see impressive phenomenon and maybe, a few gulls along the way.

Timing was everything at the bank. Afterall, the River Mersey was still tidal all the way to Warrington, so getting your visit to coincide with the right tide was essential; get it wrong and the bank could be completely covered by water and devoid of gulls. Tide tables therefore became a prerequisite, but it was not just the time of the tide but its height too which became important. To maximise our available visits, we quickly worked out at what height the tide actually covered the bank. Now this wasn’t necessarily always as easy as it sounded as being made of mud, the bank was always changing shape. Sometimes it was really flat and covered very easily and others it was huge, with great three-foot sheer cliff edges which could withstand all but the very highest tides, so you just never quite knew until you got there, but we still tried our best. Only on those very highest tides was it ever covered for any real length of time though and so when the average high tide fell slap bang in the middle of our visit, we’d usually sit it out. This gave us chance to eat and drink, chat or indeed, watch Jeremy Kyle but it never lasted more than an hour, for the gulls knew when the tide was ebbing and would be quickly onto it, wading around until the first mud became exposed once more.

It was those very highest tides which became something of a fascination to us though. The really big tides above ten metres, especially the ones usually occurring in spring and autumn, would completely flood the area, very rapidly swelling the river over its banks, swamping the grassy edges. Whilst they weren’t always conducive for gulling with the height of them meaning the bank was well covered for a couple of hours at least, we still went down to catch maybe an hour or so before its peak but more importantly, to watch the tide itself. It was just a great spectacle. The sheer volume of water and speed of the deluge was impressive alone and the amount of detritus it would carry up stream (and back down again later) was remarkable. It would often flush out hidden Snipe and occasionally, one or two larger looking pipits with explosive single note calls which never did give anything other than very fleeting flight glimpses; Rock or Water…that was the question. As the water rose, the bank itself would become smaller and smaller, with the gulls corralled into a tight white horde as they fought to remain on the mud for as long as possible before being forced off back to the tip or downstream for the rest of the day as it was enveloped.

It was only on very rare occasions that we experienced the most impressive spectacle the Mersey had to offer though. It was early spring the first time we witnessed it. Pete and I were searching through the thousands of gulls as usual when I heard a noise coming from downriver, heading upstream towards us. I expected it to be a boat of some form as I couldn’t quite place the sound, a roar of kinds, and boats were occasional past the bank and a bloody nuisance to boot. As the roar became louder, it finally rounded the bend in the river and came into full view. Now, a twelve inch wall of water moving at running speed up the width of a river and against the flow might not really sound all that impressive but let me tell you…it is. Up to that point we had no idea the Mersey even had a tidal bore and it seemed neither did the equally surprised gulls but sure enough, there it was in all its, admittedly not exactly surfable, glory. So taken we were with it we would work out when the next one was likely to be and make further visits just to see impressive phenomenon and maybe, a few gulls along the way.

A rapidly rising tide at the bank forcing the gulls into a tightly packed scrum on the disappearing mud and their watchers into feverish scrutiny ahead of the imminent exodus.

REGULAR, RARE AND NEVER AGAIN

We certainly weren’t the initial pioneers of gull watching at Richmond Bank. They had been watched there before our initial visits, though it has to be said, perhaps not quite as comprehensively, nor vigorously, as we undertook over the years. It had been pretty poorly watched on the whole though and in those early days it was mainly down to regulars like Pete and I and a few scouse gullers. Of course, as we began to pull those scarcer and more desirable species out of the larid throngs it certainly started to become more popular. This was coupled with a distinct heightening in the understanding, publicity and popularity of Caspian Gulls at the time and the fact that the bank afforded the best chance of acquainting yourself with the species, which for many back then, would be a first. The ‘Caspian heyday’ indeed.

In those heady days of discovery and particularly at weekends, observer numbers swelled to their peak of mob proportions, a melee of chairs and tripods, of clamoured directions and boisterous chatter, usually about holidays or rarities elsewhere, but rarely about gulls. I began to avoid weekends. I much preferred the quiet calmness and solitude of weekdays but of course, once they’d ticked off Caspian Gull, most rarely came back again anyway. After a season of bank adoration for many, it was back to just the regulars, though our numbers expanded slightly by those who had become infatuated with gulls and who sought to learn more, though as is often the case, even for them that love didn’t last forever. There were plenty of observers who only ever came to the bank once too. Sat bemused in front of several thousand gulls, they were simply overwhelmed to the point they never came again. It all looks so simple in the pages of a field guide or perhaps at a small local gull roost, so seemingly black and white. In reality though, when faced with such a massive diversity of species, ages, moult, wear, shapes and sizes all in the one location, it became much more confusing shades of grey and the sheer variety would fry the brain of those admittedly ‘trying to get into gulls’.

In order to spend up to maybe 15 hours a week looking at them, you simply have to love gulls. The challenge they afford, the hilarity of their behaviour, the beauty of their guise. It isn’t for everyone and it certainly wasn’t at the bank, but many tried, came and went but no one conquered, not even us regulars. The gulls and the mud of Richmond Bank always had the upper hand.

We certainly weren’t the initial pioneers of gull watching at Richmond Bank. They had been watched there before our initial visits, though it has to be said, perhaps not quite as comprehensively, nor vigorously, as we undertook over the years. It had been pretty poorly watched on the whole though and in those early days it was mainly down to regulars like Pete and I and a few scouse gullers. Of course, as we began to pull those scarcer and more desirable species out of the larid throngs it certainly started to become more popular. This was coupled with a distinct heightening in the understanding, publicity and popularity of Caspian Gulls at the time and the fact that the bank afforded the best chance of acquainting yourself with the species, which for many back then, would be a first. The ‘Caspian heyday’ indeed.

In those heady days of discovery and particularly at weekends, observer numbers swelled to their peak of mob proportions, a melee of chairs and tripods, of clamoured directions and boisterous chatter, usually about holidays or rarities elsewhere, but rarely about gulls. I began to avoid weekends. I much preferred the quiet calmness and solitude of weekdays but of course, once they’d ticked off Caspian Gull, most rarely came back again anyway. After a season of bank adoration for many, it was back to just the regulars, though our numbers expanded slightly by those who had become infatuated with gulls and who sought to learn more, though as is often the case, even for them that love didn’t last forever. There were plenty of observers who only ever came to the bank once too. Sat bemused in front of several thousand gulls, they were simply overwhelmed to the point they never came again. It all looks so simple in the pages of a field guide or perhaps at a small local gull roost, so seemingly black and white. In reality though, when faced with such a massive diversity of species, ages, moult, wear, shapes and sizes all in the one location, it became much more confusing shades of grey and the sheer variety would fry the brain of those admittedly ‘trying to get into gulls’.

In order to spend up to maybe 15 hours a week looking at them, you simply have to love gulls. The challenge they afford, the hilarity of their behaviour, the beauty of their guise. It isn’t for everyone and it certainly wasn’t at the bank, but many tried, came and went but no one conquered, not even us regulars. The gulls and the mud of Richmond Bank always had the upper hand.

Eyes on the prize. One of my first self-found north-west England Caspian Gulls on the bank back in 2010 as submitted to CAWOS and a subsequently well watched bird, one of the first to be really unblocked for many observers in the north-west.

CHAIRMEN

Gull watching is a very sedentary pastime. As someone who usually doesn’t like sitting in hides or standing around and much prefers a good mooch chasing tails and kicking bushes, it’s something of a surprise that it appeals to me so much. You basically wait for the gulls to come to you over a period of up to several hours and as such, combined with periods of inactivity save for the occasional unscrewing of a thermos, scribbling in a notebook or feverishly grabbing a camera, that means you need something to sit on.

On our early visits to the bank we made do with what we could find, which rather fortuitously was initially an old wooden garden bench. Once that had disappeared though we started to bring our own. I went for the cheap and cheerful canvas collapsible camping chair as did Pete, though mine lasted years Pete’s didn’t and was replaced with the simple folding style chair he still has to this day. Over the years we saw them all come and go though.

Most birders turned up with fairly modest, lightweight items, sensible seeing as it was a fifteen-minute walk to lug it from the car to bank, but whether there was some one-upmanship at play, others took a different slant. Camping chairs started to gradually get bigger. They started to feature much more padding, and big wide girths like bouncy castles on legs, even with side tables too, though the joy they gave us watching everything roll off every time the chair moved was worth it. Some heaved utter ‘thrones’ to the bank the weight of an SAS selection Bergen which would buckle the legs of any a strapping Para, like those enormous fishing chairs. One chap even turned up with all his equipment on a little wheeled trolley for pity’s sake! There’s a balance between being comfortable enough to be able to concentrate on searching through many thousands of gulls for hours at a time and taking the whole thing way, way, too far.

There were the other side of the spectrum too though…the uncomfortables. Little tiny tripod like camping chairs which made the user look like they were sitting on a toadstool, their limbs all bent up like a pretzel; a beer crate; a shooting stick; their eight-year-old daughter’s deckchair. Some sat directly on the floor (so you couldn’t even see above the grass!) or even just plain stood up, though the latter unsurprisingly never did last more than the odd hour. Pride of place though went during a period of particular observer popularity when well into double figures could be present looking (or at least supposed to be looking) at the gulls. I will never forget that one-man pop-up style camouflaged hide, nor the occupant constantly craning his head out of the front window asking what we were all looking at or indeed, what he’d missed. What are some people thinking?

A medley of chairs on display, including Pete Berry far right, who clearly liked to sit on his at a jaunty angle just for kicks.

WEATHER OR NOT

The weather played a large part when planning our visits to the bank. Let’s face it, it’s not ideal sitting in torrential rain for hours and certainly in the early days we’d avoid days of forecasted precipitation. We quickly learned though, that the weather forecast is something of a hit and miss process and despite their millions of pounds worth of meteorological equipment, we were missing valuable gulling time due to rain not stopping play as predicted. So, we took to taking large umbrellas with us on days they forecast rain, so desperate were we to not to miss any action and it worked well too. You could easily hold an umbrella in one hand and scan using the ‘scope with the other, defying rain so long as it was driving in from a generally westerly direction (so the rain was coming from behind us), which rather fortuitously it more often than not was. We went through a few umbrellas of course, mutilated by strong gusts of wind or gashed by thorny bushes on the walk down. Pete once brought a huge fishing umbrella which could fit us both under with ease and also had guy ropes to tie it down against the wind. It was a brilliant bit of kit but walking down there with our chairs and this huge umbrella (which was so heavy we had to take it in turns carrying along the way) it looked like we were setting up shop with a full set of patio furniture. So, we learned to work around the rain and the same went for the cold too.

Being a mainly winter pursuit, sat arounds watching gulls all day was a generally very cold affair. Our wardrobes quickly burgeoned under the featherlight weight but big, bulky proportions, of down jackets fit for climbing the Matterhorn itself, so Richmond Bank was a mere walk in the park. Thick skiing trousers and gloves were de rigueur, the latter so thick you could just about turn the focus wheel of an ATS 80 but had no chance with the level of dexterity required to take the lid off a thermos or unfurl tin foil wrapped sandwiches, let alone utilise a pencil or shutter release button. On one infamous occasion we sat for four hours in minus five Celsius. The bank itself was covered in a thick and craggy sheet of ice and snow and large icebergs floated down the river, some lodging themselves on the bank, all making for a quite surreal panorama. Eventually, the frozen ground beneath our feet struck through our boots and even skiing gloves had their limits and yet again, the bank laughed longest.

In fact, the only weather condition we really steered away from was strong sunlight. Such sunlight at the bank completely obliterated any genuine appreciation of colours and hues for starters. The dark greys of Lesser Black-backed Gulls started to look paler, burned out by the sun and for some, confusingly Yellow-legged Gull like, often causing a spike in claims when coinciding with those big spectator days. Worse still, the heat haze across the mud arose with even the slightest sniff of warmth and in a pursuit where optical magnification is king when gorging on key identification minute, sunlight really was our kryptonite.

An adult Yellow-legged Gull amongst not dissimilar argenteus and argentatus Herring Gulls, but with the gift of lovely flat light at least making grey colour assessment much more accurate.

A Caspian Gull like this beauty made any day at the bank well worth the effort, with it positivity glowing amongst its dingier cousins.

GREAT EXPECTATIONS

You could pretty much always expect gulls on the bank. Other than a huge tide or perhaps the occasional cretin with a shotgun which could ensure the area was devoid of them, there’d usually be a constant flow throughout the day. Either way, there was always a good measure of expectation as you made the walk to the bank, followed by a little relief at your first glimpse of the thousands of gulls waiting to be poured over.

Out of the many thousands of gulls present, rarer species like white-wingers, Yellow-legged and Caspians formed only a diminutive percentage and in order to pick them out considerable patience, effort and perseverance were usually necessary. It wasn’t all gulls though. Sitting in the same spot for hours on end could be really productive and was certainly energy efficient and with it we saw some good ‘non-gull’ birds too. We had the odd wader, though nothing too surprising, like Grey Plover, Knot, Sanderling, Greenshank; Little Egret and once a Bittern; Marsh Harrier; Ring-necked Parakeet; Tree Sparrow; Merlin; Yellowhammer; Willow Tit; Brambling; Whooper Swan; Short-eared Owl; and best of all one March, a pair of Firecrest which came to get a close look at us sat on deckchairs amongst the bushes; the male even sang, no doubt in sheer disbelief at the two idiots. They were all just ‘padders’ though and gulls rightly formed our main diet at the bank (other than a feeding Common Seal which delighted us one day) and for variety, sheer numbers and accessibility for viewing, the bank was simply unrivalled in the north-west of England and could give anywhere else a run for its money too.

Ten species of gulls seen in a single day was achieved a few times and our daily record for Yellow-legged Gulls stood at a very north-west England impressive thirteen. If you were very lucky you might pick out five or maybe even six different white-wingers in a day but there was usually at least one or two present on most winter visits. Caspians were much scarcer though but over an eight-year period I recorded twenty four individuals; an average of just three per year. There were plenty of gulls which defied positive identification too, mostly regarded to be just weird and wonderful commoner species or hybrids but some, were maybe much rarer. The whole period was just one big schooling, immersing yourself into the deep, dark world of gull mystification.

Perhaps that was the biggest expectation we had of the bank. That it would present us with infinite questions and make us work hard for the answers. That it afforded us a genuine opportunity to further our knowledge and understanding of gulls but ultimately, provided us with sheer enjoyment, delight and experience. Along the way we also made great memories and friendships that defy the virtual reality in a great deal of modern birding and for that Richmond Bank, we salute you.

You could pretty much always expect gulls on the bank. Other than a huge tide or perhaps the occasional cretin with a shotgun which could ensure the area was devoid of them, there’d usually be a constant flow throughout the day. Either way, there was always a good measure of expectation as you made the walk to the bank, followed by a little relief at your first glimpse of the thousands of gulls waiting to be poured over.

Out of the many thousands of gulls present, rarer species like white-wingers, Yellow-legged and Caspians formed only a diminutive percentage and in order to pick them out considerable patience, effort and perseverance were usually necessary. It wasn’t all gulls though. Sitting in the same spot for hours on end could be really productive and was certainly energy efficient and with it we saw some good ‘non-gull’ birds too. We had the odd wader, though nothing too surprising, like Grey Plover, Knot, Sanderling, Greenshank; Little Egret and once a Bittern; Marsh Harrier; Ring-necked Parakeet; Tree Sparrow; Merlin; Yellowhammer; Willow Tit; Brambling; Whooper Swan; Short-eared Owl; and best of all one March, a pair of Firecrest which came to get a close look at us sat on deckchairs amongst the bushes; the male even sang, no doubt in sheer disbelief at the two idiots. They were all just ‘padders’ though and gulls rightly formed our main diet at the bank (other than a feeding Common Seal which delighted us one day) and for variety, sheer numbers and accessibility for viewing, the bank was simply unrivalled in the north-west of England and could give anywhere else a run for its money too.

Ten species of gulls seen in a single day was achieved a few times and our daily record for Yellow-legged Gulls stood at a very north-west England impressive thirteen. If you were very lucky you might pick out five or maybe even six different white-wingers in a day but there was usually at least one or two present on most winter visits. Caspians were much scarcer though but over an eight-year period I recorded twenty four individuals; an average of just three per year. There were plenty of gulls which defied positive identification too, mostly regarded to be just weird and wonderful commoner species or hybrids but some, were maybe much rarer. The whole period was just one big schooling, immersing yourself into the deep, dark world of gull mystification.

Perhaps that was the biggest expectation we had of the bank. That it would present us with infinite questions and make us work hard for the answers. That it afforded us a genuine opportunity to further our knowledge and understanding of gulls but ultimately, provided us with sheer enjoyment, delight and experience. Along the way we also made great memories and friendships that defy the virtual reality in a great deal of modern birding and for that Richmond Bank, we salute you.

Not what you expect to see, but a genuinely melanistic Lesser Black-backed Gull was possibly the rarest gull recorded at the bank!

The big one that got away though? It could never be proven and really, I need to let it go; so it can just sod off!

Richmond Bank remains of course. The slowing flow of the Mersey as it widens will always continue to deposit mud there but for gull watching, that chapter is concluded. With the closure of many refuse tips and the tenuous future for those which remain, the prospects for gulls and certainly their watchers are perhaps uncertain too. There is absolutely no doubt that gulls are an immensely hardy and adaptable bunch and they will survive come what may but us gull watchers, those who experienced first-hand the hedonistic days at the bank, are finding it much more challenging to cope.

Farewell Richmond Bank, farewell. It was a blast.